Every instructor is familiar with this scenario: take 10 students and teach them the same Open Water course, and 6-7 will be competent, 2-3 will be excellent and 1-2 will be at the cusp of acceptability – they may meet all the skill requirements, but the instructor knows in his/her heart that this student is not yet ready to dive independently.

There could be many reasons for this, but a common (and often-ignored) cause, and the subject of this article, is kinesthetic awareness (or K-Factor, to coin a sexy phrase) or lack thereof.

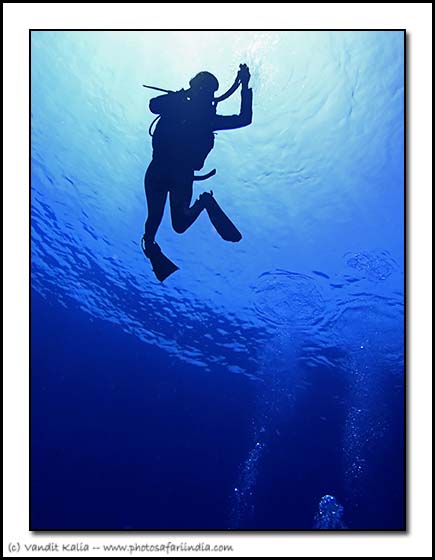

A student’s first immersion in water leads to a lack of physical coordination – gravity, balance and force don’t work the way they are used to. The weight shift that they use on land for balance correction only causes them to topple over. Using their arms for balance doesn’t help. Their body simply doesn’t behave the way they expect.

Most students start adapting very soon – I typically see a big improvement about half-way through the confined water session, and then on each additional dive. In fact, this continues all the way through to Advanced Open Water (which leads to my article on when to do the Advanced Course, but that is a separate topic). Slowly, they realize that doing A and X leads to C and Z underwater, and not B & Y, and their brain starts to build the neuro-muscular patterns needed to replicate this. This process is very similar to the way you learn to play a racket stroke, golf swing, basketball shot, etc. etc. In other words, the student starts to gain a new set of kinesthetic awareness for the underwater world. When this happens, it is as if a switch has come on – they slow down and stop fighting the water, their movements become deliberate, their buoyancy improves and they no longer resemble puppies on speed underwater.

But what about the small percentage of students who simply continue to fight it and simply don’t gain that K-Factor?

Let me go off on a seeming tangent now and talk about a dive industry secret that you don’t know, or whose implications you have not considered. The secret is this: the role of most dive agencies is not to product highly-qualified divers, but to make diving accessible to as many people as possible while maintaining acceptable levels of safety.

And for the record, while this approach is far from perfect, I am not saying it is inherently a bad thing. If you want to ski, do you need to be an expert skier who can handle black diamonds before being let out on the slope? Of course not. You merely need to learn the basics and then you go forth and ski, and continue to develop skills (this aspect – of continued skill development – is often ignored by the doom’n’gloom brigade who rend their garments and beat their chests at the state of diving today).

In a similar vein, diving courses tend to focus on teaching the basic, specific skills needed to dive safely – how to clear your mask, how to share air, how to achieve neutral buoyancy, etc. After that, you go forth and continue to develop those skills and have a bunch of fun in the process.

Using Bloom’s taxonomy, the focus in entry-level training courses is on getting up to the Comprehension level in the Cognitive domain, and Mechanism stage in the Psychomotor domain. Sure, a conscientious instructor might go up one or two stages higher in each of these domains, and also perhaps up to the Valuing stage in the Affective domain, but strictly speaking, it is possible for a student to get certified if they merely achieve the above-mentioned two stages.

Leaving jargon aside, what does this mean in reality? It means that if the student is able to understand dive theory to the point of being able to pass the exam (Comprehension) and able to satisfactorily perform a set of complex tasks (Mechanism), then he is ready to be certified – which, as we all know, is not the same as being qualified.

Oh come on, Vinnie, you are such a pessimistic cynic, you say. My students do a lot better than that, and are able to apply the information I have taught them to new situations [Application and Adaptation], you claim.

Sure. A lot of instructors do ensure that their students are able to integrate what they’ve learned, and actually master the motor skills they were taught, to the point that they can apply them with some situation-specific modifications as needed. However, my point is that due to the focus of the dive industry in making sure diving is accessible to as many people as possible, teaching standards of most agencies are focused on achieving basic competency and safety, that’s all.

So now let’s go back to our student diver who has successfully completed all the skills but hasn’t stopped fighting the water yet.

Any instructor who cares about producing qualified divers (and sadly, this breed is not as common as you would think, given that scuba is a passion-driven sport) will not just hand out a C-card to this student. However, this where the support system provided by the agencies tends to fall apart.

While experienced instructors usually develop, through trial and error, their own set of exercises to help such a student achieve aqua-zen, newer instructors are often left to their own devices in such cases. Some of them give up on the student. Others just say eff it and certify the student, to ensure that they get their salary commission or meet their targets. Yet others waste time repeating buoyancy drills or mask clearing drills or whatever, sometimes frustrating the student to the point where they are put off diving for good.

Not surprisingly, as there is nothing in any Open Water curriculum I have seen that even discusses this problem, let alone give tips on how to solve it.

As such, I’d like to address this gap by suggesting a few tips of my own for teaching kinesthetic awareness to students – and do note, these tips are by no means exhaustive, there is some overlap between the concepts in them, and there are plenty of other ways to teach this as well. These are simply tricks that have worked for me and instructors I have taught/worked with.

1/ Start by making sure kinesthetic awareness is the issue, not something else

Sounds obvious, doesn’t it? But accurate diagnosis of the problem is often harder than it seems. As instructors, we all know what the critical attributes for a particular skill are, and how to pinpoint skill mistakes by checking the critical attributes. But when a student is fighting the water, it is harder to figure out if it is a matter of nervousness/fear of the water, lack of the K-factor, or a specific lack of knowledge on how to perform a specific skill. To complicate things, nervousness can be increased by the lack of K-Factor, and vice versa. While there are some things that can indicate a likely reason, they are not reliable and my goal with this article is not to handhold anyone (or provide guidelines which can be mis-interpreted as rules), so I am not going to get into specifics – suffice to say, simply by knowing the possibilities, you can start the process of eliminating them by observing and chatting with the student.

2/ Allow the student to struggle a little

Yes, that is correct. A lot of instructors will pile on with a bunch of instructions, signals, exercises, etc. right at the beginning. I suggest the opposite approach – let the student struggle a little with flappy hands, moving around a lot, etc. and then start to work on specific exercises to correct them. Now, the trick is to only let them struggle only a little – too much, and they start to build in bad habits or get discouraged. And needless to say, the struggle should be purely with motor skills, not mental or physical stress. The benefit of this is that the student has a first-hand experience to draw upon when you explain how to correct the problem.

For example, when I teach confined water, I initially do a short underwater swimming without any briefing on buoyancy, use of the BCD or lungs. We just go for a swim. Then I give each student one specific thing to try on the next swim. And so on.

3/ One thing at a time

It is very easy to overload someone with a low K-factor by giving them a complicated briefing with multiple sub-skills. For that reason, it is best to work in small steps and give them one thing to focus on. Give them time to experiment and truly absorb what happens when they try that one thing you have told them to work on. Once they get the hang of this, then go to the next one.

Hovering and neutral buoyancy is a skill where people with poor K-factor usually struggle: so usually I start by having them focus on one thing only – using their lungs to inhale/exhale and see what happens. They are encouraged to experiment with different breathing patterns in an effort to imprint upon their brain the relationship between breathing and buoyancy. At this point, everything else is secondary. Once they get this, then we go further.

Usually, each step in this process is related to the errors that have led to the struggling.

4/ Work on breathing and balance

The best way to learn proprioception (another fancy word for K-factor) this is to simply spend time in the water and feeling how your body reacts. I usually tell the students to let their body

do whatever

it wants, and just focus on relaxing and breathing. As you can see, this is an application of point #3 above – i.e., one step at a time.

5/ Complex to simple works well sometimes

Usually, the best way to teach things is to keep it simply and slowly add complexity. In principle, this is correct. However, take a particular Task X, which consists of sub-steps (or critical attributes, if you will) of A, B, C and D. Each of these is a simple task, which, when done in succession, accomplished the complex Task X.

By breaking X up into A, B, C and D, you are effectively simplifying the task. At that point, you can add complexity to when teaching sub-step A. And separately to B, C and D as well. Then, when you put them all together without the added complexity, each sub-step becomes easier to perform and the overall Task X ends up being overlearned.

Case in point: for the first few sessions, I over-weight my students and have them learn to achieve and maintain neutral buoyancy while overweighted in shallow water. Then, once this is mastered, the extra weights come off – so the added complexity of swimming while neutrally buoyancy is off-set by the simplication caused by proper weighting and greater depths.

Obviously, this has to be used selectively – and generally, it is effective only if it meshes with the overall geshtalt of your teaching style and progression. So dont go rushing in and making everything complicated right from the get-go. But if done right, especially for certain specific skills and within the proper framework of your overall teaching progression, it is a very powerful technique.

6/ Reduce pressure – allow student to practice on their own

There is a difference between a student not understanding what he needs to do, and a student not being able to perform the skill. With K-Factor issues, lack of understanding is not the problem – it is the ability to perform that is. In such cases, it helps to give the student time to work at their own pace, without the added pressure of someone watching and evaluating them.

I am often surprised by how much of a difference 5-10 minutes of solo practice can accomplish, yet many instructors – fed by an agency-fuelled diet of always needing to supervise and control – find it hard to leave the student alone. Find a safe place in confined water for the student to practice, give them 1-3 simple and specific things to work on and leave them alone for a while: you might be surprised by the improvements in a short term.

7/ Give them time

Sadly, there is no shortcut here. You cannot teach K-Factor, the students have to acquire it themselves. And nothing beats time. Obviously, there are limitations on time imposed by external factors, and there, each dive center has its own policy. I would encourage instructors to ensure an environment which minimizes time-related stress for the student – and by time-related stress, I include cost-related stress as well: i.e., “If I don’t learn it now, I will lose $X or have to pay $Y for more training”.

I realize not every dive center can operate this way, but our approach is we charge a student a certain fee to teach them to dive – and that takes whatever time it takes. This isn’t as extreme as it sounds: with most students, even those with fairly poor K-Factors, it only requires a few additional sessions, including perhaps some solo practice time, for them to gain competency. And realistically, a student who has such poor K-Factor that he need substantially more time is probably not ready to be certified at this point of time anyway.

8/ Non-scuba skills work

Snorkeling, skin-diving and even swimming sessions are a good way to build K-Factor. And as an added bonus, a lot of this practice can be done outside training time.

The Total Immersion swimming books and videos have a couple of good drills on teaching balance – these are primarily geared towards swimmers, but I have found that the same balance drills are actually very helpful for students with acute K-Factor issues. Because practising these drills do not require scuba gear, the student can work on their water balance in a pool or beach-side, between training sessions or even after certification.

9/ Teach relaxation

Try this – unclench your stomach and your glute muscles. When you do, your whole body relaxes. In martial arts, when doing chi-flow exercises, relaxing/tightening the core is one of the basic exercises for developing chi flow. On a more prosaic level, it is impossible to be stressed, struggle and to retain air in your lungs when your stomach and butt muscles are relaxed. When a student focuses on this aspect, he is too busy to struggle in the water – in the meantime, his subconscious brain is busy learning proprioception and re-wiring his neural system accordingly.

10/ Patience and communication

As an instructor, it can sometimes get frustrating. You pride yourself on the thoroughness and efficiency of your teaching, and of how good your typical student looks in the water when done. And now you have someone who simply refuses to absorb your training. Even the most patient of instructors will have a few “COME ON ALREADY” moments. I have to admit, I have.

However, in such cases, it helps to realize that if you are frustrated, the student is doubly so. He is seeing you looking graceful in the water (as an instructor, you DO look graceful in the water, right?), he is seeing the other students doing the same thing a lot more easily – and you can be sure, he is frustrated by his own struggles.

This can make him stressed, which leads to clenched stomach/core and greater air retention in the lungs, which in turn leads to greater struggles. This can also lead to finding excuses – this isn’t working, I don’t have enough weight, etc. etc.

As an instructor, you need to find the right balance between being encouraging and positive, and at the same time, not wasting too much time entertaining false excuses.How you deal with it varies depending on you, the student, the dynamic between the two of you and the situation, and can range from gentle encouragement to firm instructions and even tough love. Regardless of how you choose to handle it, use empathy (not sympathy, mind you – the two are different) to understand what the student is feeling and figure out the best way to get them to improve.