PUTTING TOGETHER AN UNDERWATER PHOTOGRAPHY SYSTEM BASED ON A COMPACT CAMERA

Are you interested in taking high quality underwater photos? Or perhaps upgrading from your GoPro to something that takes better images and also is more scaleable? Does the complexity of an underwater camera system and all the bits and pieces needed put you off buying one?

In this video and article, we are going to talk about the various components of an underwater photography system and what attributes to look for – a system that may not be the cheapest to start with, but also a system that will grow with you as your interests develop (which works out to better value in the long run).

For the purposes of this article, we are going to ignore ILC (Interchangeable Lens Cameras, like DSLRS and Mirrorless) – while they are technically the best solution, they also require a commitment in terms of money and approach to diving that is not suitable for most people, atleast not initially. For the vast majority of divers, a compact camera system actually is the better tool.

1: THE CAMERA

When picking a camera, the obvious point is to make sure there is a housing that is made for that specific camera model. That aside, please look for one with the following attributes:

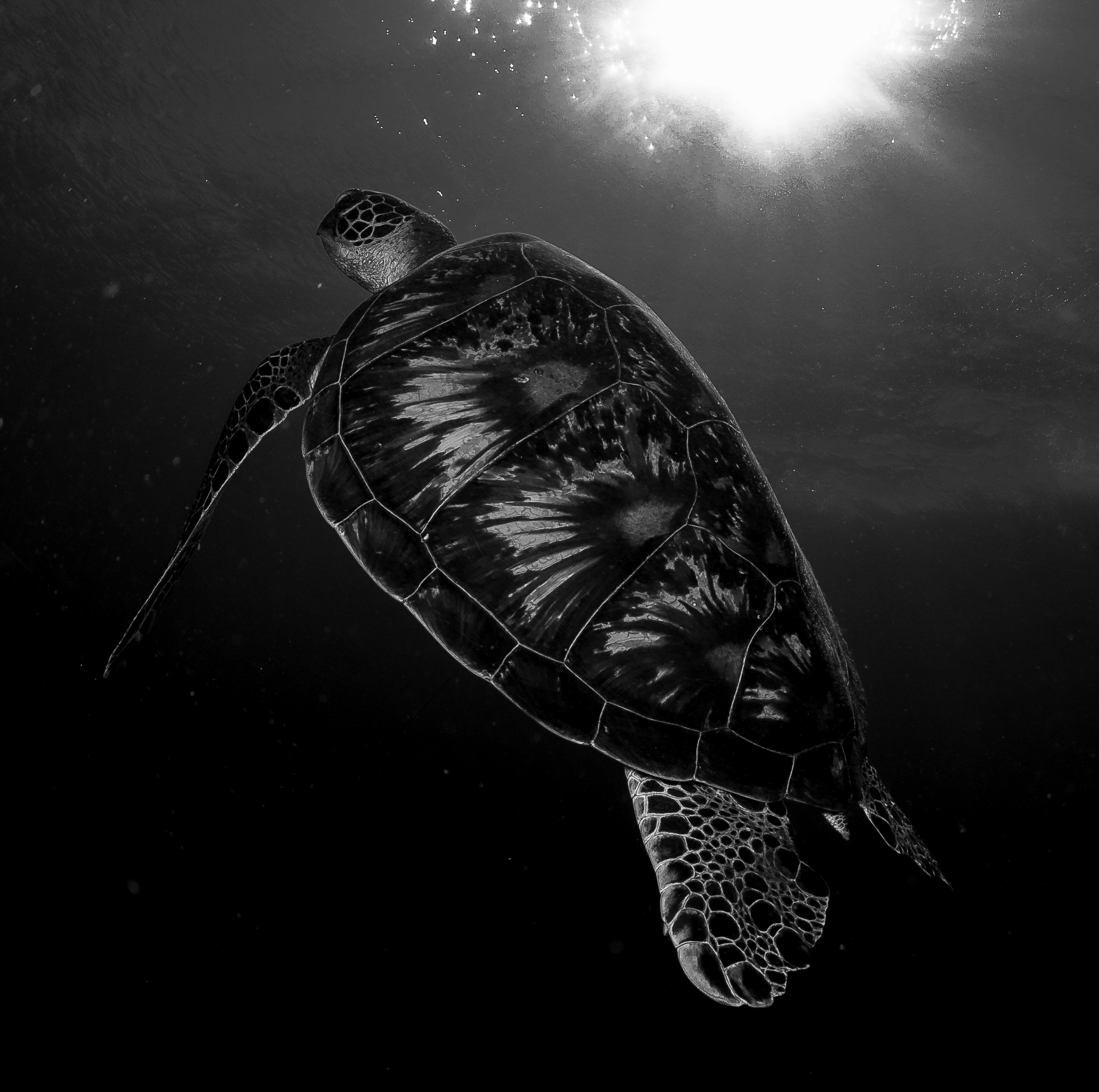

- A good wideangle – the wider the better: Underwater photography is all about getting close to your subject, and a wider angle lens lets you get closer to subjects ranging from turtles, large coral outcrops, divers, etc. This means that your images are going to be better lit, sharper and have more detail/contrast. By contrast, the telephoto range is not as important, as you will rarely be shooting something too far way.

- A good close-up/macro mode: Among the most rewarding – and easily accessible – category of subjects in underwater photography are macro subjects: nudibranchs, shrimps, etc. And here too, you want to get as close as possible, to fill the frame with your subject.

- Fast autofocus: While modern cameras have improved substantially compared to the Olympus C3000 I started shooting with, back in 2001, there still is a difference in autofocus, especially in poor light and low contrast (ie, your typical dive). Faster AF will result in a much greater percent of keepers, especially for fish portraits.

- Easy to access controls: Operating a camera underwater means working through a housing, which is typically via buttons and dials. A camera which requires a lot of use of touchscreen or rotating dials typically does not pair well with these buttons and dials, and so may limit your ability to set key parameters underwater.

- Built-in flash: One feature I didn’t mention in the video is a built-in flash, mainly because virtually every camera does come with a flash. This is mandatory – that built-in flash is what controls your strobe (see section 3). No flash = no strobe, and you might as well just shoot with a GoPro.

In addition to this, a nice-to-have feature (for me) is built-in waterproofing. This way, if or when the housing floods, there is a good chance you may save the camera. You can also use the camera for other activities associated with the diving trip – beach, snorkelling, etc. and not have to worry about it getting splashed.

This is the camera I used underwater (at the time of writing this article): an Olympus TG5. It has the best macro modes out of all the compacts in the market at present

As camera housings are specific to individual cameras, you obviously need to pick a camera model which has at minimum a housing made for it and ideally, a range of accessories to support the system. The 3 brands which I recommend are Canon, Olympus and Sony. Each of them make cameras that are very popular with underwater photographers, and so it is easy to find housings and other accessories for them.

Do note – if you have a compact camera already, you can likely get a housing for it and wont need to buy a separate camera. However, I do encourage read up on the housing section to determine what features to look for when it comes to building a scaleable system, and whether you particular camera + housing combo meets those requirements. In some cases, it may be better in the long run to buy a new camera, rather than build a compromised system around a less-than-ideal camera.

2: THE HOUSING

The housing is the waterproof case within which the camera is kept while shooting underwater. When looking for a housing, look for the following 3 main attributes:

- Ergonomics: What you want is a housing which feels easy to grip in your hands and where the important shooting controls – focus, change AF point, change exposure – are easy to reach with your fingers, without you needing to take your hand off the grip every time. I cannot overstate what a big difference this makes when you are actually shooting – if you are struggling with your camera, you will not be able to get the best shots.

- Access to controls: Most camera housings do give access to all the essential controls when shooting underwater – however, in several cases, many “nice to have” functions may not be accessible. For example, if you rely on a particular custom function button or a rotating control dial, please make sure you can access it from within the housing.

- Ability to easily add accessories: This is the single biggest attribute when it comes to determining whether your system will scale up or not. As your needs evolve, you may find you want greater close-up capabilities or the ability to go wider for impressive reefscapes. Does your housing allow you to add these components easily? At a more basic level, can you connect to your strobe using standard connectors or are you dependent on proprietary connectors that limits your choices? Ideally, you want a housing with a threaded filter mount in the front, which will let you screw in additional accessories and a port for plugging in an optical fiber cable to sync your external strobe with the camera’s strobe.

This is the Olympus PT-058 housing I use with the TG5. The front of the port has 58mm threads for screw-in accessories and there are 2 ports for fiber optic cables on the upper right of the port – allowing me to attach 2 strobes directly to the camera

Housings can be made by the OEM (camera manufacturer) or by a third-party manufacturer like Nauticam, Fantasea, Seafrog, etc. OEM housings are generally relatively inexpensive and made of polycarbonate. Third-party housings often tend to be a bit more expensive, and often made of metal.

Often (but not always), third-party housings may have a better ecosystem of accessories – which is a good reason to pay a premium for them. In addition, while OEM housings are typically rated to 30m or 40m, metal third party housings may be rated to 60m or deeper – for divers looking to shoot at tech depths, a more expensive 3rd party housing may often be the only solution.

The housing has a large window in the back for looking at the LCD screen and all the buttons are large and easy to access

However, purely in terms of reliability and functionality, I have not found 3rd party housings to be more reliable or less prone to flooding. Personally, as long as the housing met my preferred depth rating and checked off the three attributes listed above, I would happily buy the cheapest housing – as long as it was from a reputable brand. There are plenty of horror stories about ultra-cheap housings flooding due to poor QC – that is not a risk I am willing to take, so save $100-200.

The shutter button has a large lever, making it easy for most hand sizes, and the zoom and power buttons are also easily accessible. There is also a cold shoe on the left, for mounting additional accessories

3: THE STROBE (UNDERWATER FLASH)

Photography is, in its essence, the act of recording light. It doesn’t matter how expensive your camera – if the light is poor, the image will be poor. And underwater, the natural light is always poor: you will need a powerful flash to not just brighten the scene but also to add in the reds that have been absorbed by the water.

Simply put – the strobe is the single most important element in taking high quality images. Period. This is one area where you should not skimp (and unfortunately, this is the one area where most people do try to cut corners). A good strobe has the following attributes:

- Power: Power is represented by something called Guide Number. Without getting into the specifics of what it means, the main thing to know is that bigger = better. You want as high a GN as possible – ideally, atleast 20-22, or even more if budget allows. Once the payment is made, you will never regret having a more powerful strobe.

- Angle of coverage: Along with power, you also need to know the angle of coverage of the strobe beam. Many cheap strobes may appeal due to their high GN, but the angle of coverage is very low, which can be a problem when it come to lighting a scene. You want an angle of coverage of atleast 90 degrees – and as before, more if you can afford it.

- Beam uniformity: This is another area where cheaper strobes cut corners. A good strobe will have even lighting across the entire beam. No hotspots, which can cause uneven exposure when shooting underwater

- Manual controls: Most strobes have an automatic mode, where they work seamlessly with the camera’s TTL exposure mode (unsure what TTL is? Just think of it as fully automatic, with the camera effectively controlling the strobe). This is great when you are starting out or for macro, but auto mode is unreliable with many subjects, such as wide angle and reflective fish. For more consistent results, you want the ability to set the strobe’s power manually. This is a lot easier than it sounds, and is something many photographers gravitate to as they evolve. Is it essential? No. But having this feature ensures you will not outgrow the strobe.

- Additional features: These include things like focus lights, torch functionality and red light (for focus assist in the dark with shy subjects). While not essential, they do make your diving a lot easier – which is always nice.

The Inon Z240 (top of the range strobe from Inon in its time) has a full array of controls and also a standard 1” ball mount for attaching to other hardware.

One thing worth noting- manufacturers often tend to be very optimistic with their claims about power and angle of coverage. And unfortunately, in the case of really inexpensive products sold on Ali Express and elsewhere, they flat out lie – and I say this as someone who uses dive lights and bicycle lights that I have bought (and will continue to buy) on those sites.

Also, video lights are not a substitute for strobes. Video lights put out a lot less power than strobes – even a $1500 video light will not have as much power as a $500 strobe. So while they may work for macro and closeup work, they are not as good for wide angle photography.

Given the importance of the lighting to underwater photography (I really think your strobes are the centrepiece of your system), I cannot overstate the importance of allocating ample budget towards them. Typically, most people skimp out and get budget strobes. Then after a few dive trips, they end up upgrading. It is better to just get it right the first time – and also more economical in the long run.

It is one thing to buy inexpensive torch lights or video lights (which are really torch lights with a wide angle of view) – however, the moment you add in sync circuitry and greater power needed for strobes, cheap becomes a losing proposition. I recommend Inon and Sea&Sea as 2 brands offering very good power, reliability & features for the money.

Also, as your photography skills improve, you may want to add a second strobe. But for now, it is better to start with 1 good strobe.

The controls may look intimidating, but are fairly easy – clockwise from bottom left: (1) button for turning on the torch (and locking it), (2) setting the various strobe exposure modes, (3) adjusting the strobe power in manual control modes and (4) adjusting for camera with or without pre-flash. I typically set the strobe on M on the upper left dial, and use the upper R dial to increase/reduce the power.

4: THE SYNC CABLE

This is a piece of fiber optic cable that connects your camera to the strobe – when your camera’s flash fires, that triggers your external strobe. Depending on what mode you are using, the strobe will either then put out a specific amount of light (manual mode) or will also shut off when the camera’s strobe shuts off (auto / TTL mode).

The main thing to look for is a cable whose terminators are compatible with your system. The standard used is a push fit (also known as the Sea & Sea connector, after the popular strobe maker). Inon strobes use a screw-in terminator, which is not very popular outside of Inon products, but less prone to popping out (which isn’t really a big deal, though).

The cable on the left has Sea&Sea connectors on both ends; the cable on the right has a Sea&Sea connector on one end (this plugs into the housing) and an Inon connector on the other (this screws into my strobe). You can also connect your strobe to the camera via electrical cable, but that is for DSLRs with hot shoes only, not for compact cameras.

5: THE CONNECTING HARDWARE

The camera, housing, strobe and cable are the essential bits needed to take the photo. But you also need a bunch of accessories to physically combine them into one unit and also to position your strobe underwater when shooting. These are the following:

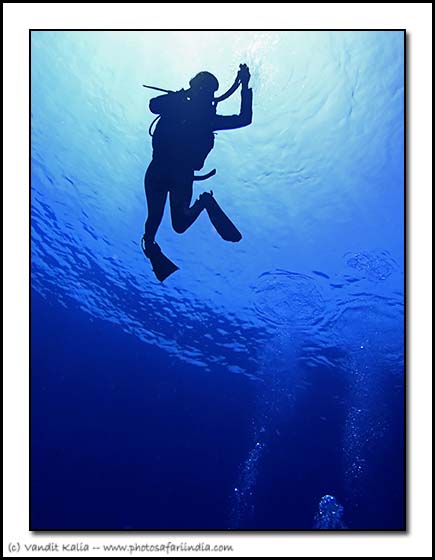

a. The base tray / handles:

The base tray is a plate that connects via a screw to the tripod mount at the bottom of most housings. It will have 1 or 2 handles on the side (depending on the option you get), for mounting most accessories.

The standard for connecting multiple pieces of hardware is 1” ball mount, as shown in the photo below. There are other connecting mechanisms as well, but try to get this, as this gives you the most options for putting together different hardware elements.

Two different trays – one is a single-handle tray (the handle actually goes on the left as my right hand holds the housing), and the other is a dual-handle tray. The latter lets you attach 2 strobes. Both the trays have the standard 1” ball head terminators for adding more hardware

b. Strobe arms:

Strobes are typically mounted on strobe arms, to get them further away from the central axis of the camera/lens (this reduces backscatter).

A common option are flex arms – they are easy to use and do not require a lot of other hardware. The downside is that they are limited in length and also positional flexibility.

Flex arms are an inexpensive solution to get started but limit flexibility when it comes to strobe positioning. Note the 1” ball heads at each end

In my opinion, rigid strobe arms are a better option for enthusiasts – by using 2 of these arms to connect each strobe, you have maximum positional flexibility for lighting (and remember – underwater photography is all about lighting). Strobe arms come in various lengths – for someone starting out with underwater photography, two 6” arms per strobe is a good starting point and well suited for everything from macro to wide angle.

Different types of arms. From left to right: 10” arms used for wide angle photography on my ILC system; 6” arms recommended for compact camera systems and 4” arms used for macro photography on my ILC system. The 10” and 4” arms have floats to adjust the buoyancy of my ILC system. As with everything else, each of these arms ends with 1” ball adapters and you can see how they connect using butterfly clamps.

As with the tray/handles, make sure you get arms with 1” ball terminators on each end.

c. Butterfly Clamps

These are clamps for connecting 2 separate hardware components, each of which has a 1” ball terminator.

For each strobe, you will need 3 of those – one to connect the handle to Arm 1, a second to connect Arm 1 to Arm 2 and a third to attach the strobe to Arm 2.

Butterfly clamps are used to join 2 separate pieces of hardware via their 1” ball heads. The nature of the ballhead and clamps allows for very easy movement underwater, along any axis

The good news is that here, you can DEFINITELY save money by buying inexpensive arms and clamps off Ebay, Ali Express or wherever. These are simple pieces of machined metal and do not require high technology or high QC – and the generic hardware costs a fraction of what the branded ones do.

So once you have a camera, housing and strobe, all neatly mounted on a tray and strobe arms, you are ready to go shooting. And indeed, you have all the tools you need to take excellent photographs – in fact, as long as you can get close to the subject and light it properly, the images from a compact camera will not be too different from that taken with an ILC.

However, where the compact camera typically falls short of an ILC is in ability to get really close (near lifesize or 1:1 reproduction) of really small objects, or its ability to encompass sweeping wide views of reefs or really large animals like whalesharks, etc.

The former requires really good macro capabilities (which most compact cameras lack – the Olympus TG series being an exception). The latter requires an ultra-wide angle of view, which is also not possible with compact cameras.

However, there are ways to get around this – by using adapter lenses. You can get close-up adapters, which let you get closer to a subject (and thereby increase magnification). You can also get wide angle adapters, which widen the field of view of the camera, thereby letting you get closer to large subjects or wide vistas. These are typically called wet lenses, as you can attach and remove them underwater. There is a small optical tradeoff compared to the specialized gear that ILCs use, but you make up for it by being able to shoot both wide angle and macro on the same dive.

6: ADD-ON ACCESSORIES

A Kraken UWL wet lens – this increases the field of view of my Olympus system from an average 100 degrees to a very wide 140 degrees: great for impressive wide angle shots.

Ability to use wet lenses depends primarily on being able to attach them to the front of your housing – typically, this can be done via a proprietary bayonet mount (specific to individual 3rd party manufacturers) or via a standard threaded screw mount (58mm or 67mm are typical sizes). I am a big fan of screw mounts, as it lets you add components from a wide variety of manufacturers.

If you are starting out, you do not need to spend money on these – but do make sure your housing has an option to add these later.

Summary

If you were looking for a magical solution to putting together a system for underwater photography on the cheap, I am sorry to disappoint. Versatile, cheap, quality – you can only pick two, unfortunately. I have chosen to focus (no pun intended) on putting together something that is significantly better than what you can shoot with a GoPro.

The system I have suggested is going to cost somewhere in the following ballpark:

– Camera: Rs 30,000

– Housing: Rs 25,000

– Strobe: Rs 35,000

– Sync cable: Rs 5,000

– Tray: Rs 2,500

– Arms + connectors: Rs 6,000

So about Rs 1 lakh / $1300 or so for the whole thing, give or take 10-15%.

Is it cheap? No. But I also think that there is no point spending $400-500 / Rs 30,000-40,000 and getting something that is only a little better – you might as well just stay with what you have. If you are going to upgrade, you might as well upgrade to something that is truly and noticeably better.

Also, it is better to spend a little more to buy the Right Stuff, as opposed to buying something cheaper which is a compromise, which you have to upgrade later. Almost every photographer goes through a stage like this (eg, with tripods) – and virtually every experienced photographer later advises against it.

If you are on budget, consider buying used/NOS. The previous generation camera and the previous generation housing can be had for substantial discounts and with relatively negligible difference in performance. Used strobes can also be a good deal, but a bit harder to source in India.

In the grand scheme of things, look at it from the lifetime utility point of view. Given how much a diving trip costs, the small increment you pay for better quality pales into insignificance, especially when you amortize it over the number of years of use you will get from it.

Anyway, I hope you found this article useful – do give us a follow on Facebook and Instagram, and perhaps share this link, if you did.