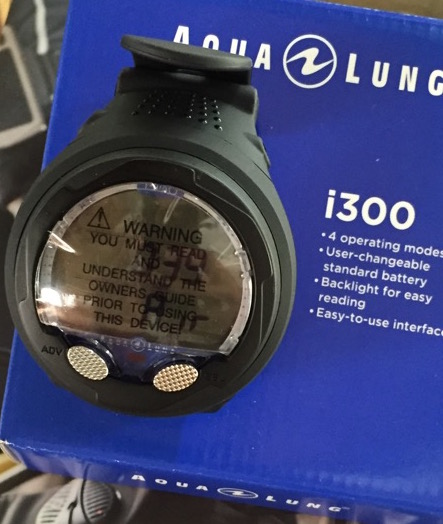

Review: Aqualung i300 Dive Computer

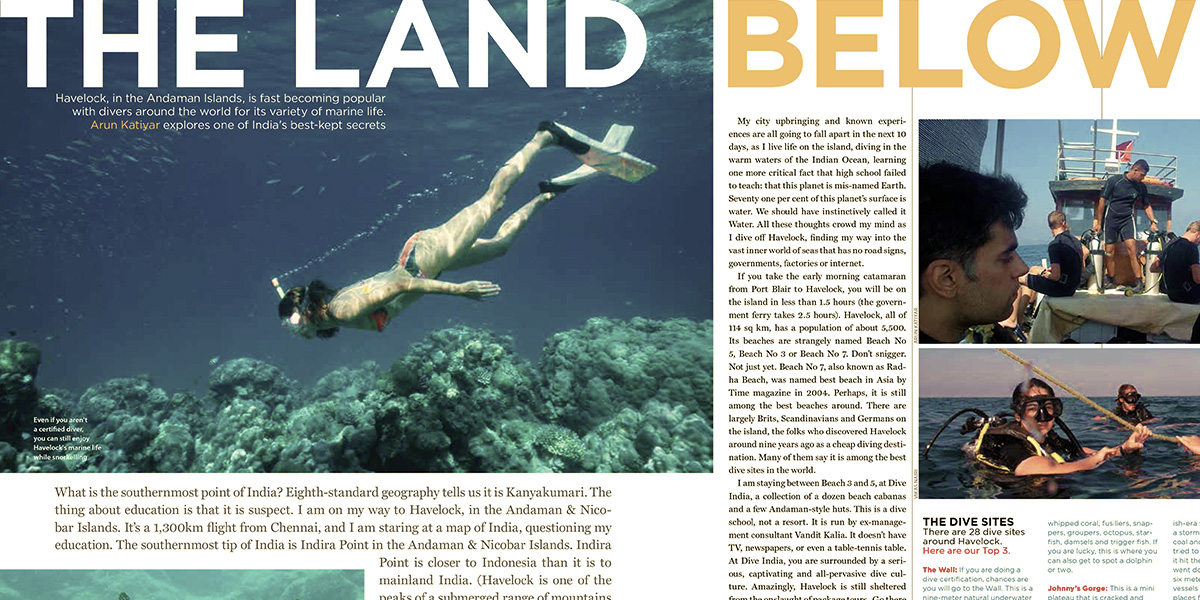

Anyone who has done an Open Water or Advanced course with me knows that I feel that a dive computer is the single most important piece of equipment a diver should own. With a dive computer on your person, you have full control over your dive and are completely self-reliant – which is exactly what you, as a certified diver, should strive to be. A divemaster or more experienced buddy is good to have as an added layer of safety, but your safety is your responsibility and no one else’s.

Yes, it costs a little bit of money – but really, if you factor in the years of use you can get out of it, the annual cost is not that high. And having all the information not only improves your safety, but your confidence as well – and that means you are more likely to dive.

At this point, I can hear someone going “yes, but i can do this with a dive table as well”. Yes, you can, in theory. I did a dive yesterday – max depth 30m, total dive time 58min and at no point did we come anywhere close to our no decompression limits. If you were on tables, you would be out of the water in 24-25 min. Do you really want to pay thousands of dollars on vacation and then give up on >50% of your dive time? Let’s get real. Dive tables are obsolete for recreational divers and for good reason.

But I digress. Getting back to dive computers: until now, it really wasn’t cost effective to buy scuba gear, including computers, in India. However, times are changing. As those of you who are members of our Facebook group know, the scuba market in India has finally evolved to the point where manufacturers are taking it seriously, and now it is becoming increasingly cost effective for people to buy gear here.

So that led to me scouring the various price lists to see if there was a dive computer that could be a sensible alternative to the Suunto Zoop, one of the heavyweights in entry-level dive computer category – and this search led me to the Aqualung i300.

Before we start, a word on ‘entry level’ – that is not the same as ‘cheapest’. The idea is to find a computer which has sensible set of features ie, one which includes everything that is essential, and where you are neither paying extra for a bunch of optional bells-and-whistles, nor saving money by giving up on things that are important (be it features or usability).

THE SPECIFICATIONS

The Aqualung i300 is an over-sized dive computer which has 4 modes: Air, Nitrox, Free and Gauge. The first 2 are for diving, the 3rd for skindiving/apnea and the last for use as a bottom timer when doing technical diving.

The first thing that jumped out at me was that the i300 has user-replaceable batteries. This is a heaven-sent. My personal computer, a Suunto D9TX, requires me to send it to Thailand every time the battery runs out – which means a couple of months without it. User-replaceable batteries are a ‘must have’, in my opinion.

The i300 also comes with a bunch of useful features: backlighting (for viewing in the dark), auto-detection of altitude and fresh water/sea water, the usual depth and time alarms & 2 unique alarms: a ‘Dive Time Remaining’ alarm (which can be set to beep to however many minutes before you hit your no-deco limit) and a nitrogen loading alarm (which can be set to beep when you hit 20%, 40%, 60% or 80% of your max nitrogen loading).

It gets credit for having a sensible Dive Plan mode – on many computers, including several Suunto models, accessing the Plan mode during a surface interval would only provide the bottom time based on the current surface interval. So if you were 30′ into the SI and wanted to get in the water after another 45′, there was no way to figure out how much bottom time you would get then – the Plan mode would only show you how much bottom time you had at that time. Thankfully, the i300 lets you add more surface time to the planning mode, which makes it actually useful for figuring out how long you have to wait or what your depth/time limits would be when you actually got into the water.

Two other neat features – it has a ‘Deep Stop’ option you can enable, if you want, and it also lets you specify the depth and duration of your safety stop.

In addition to the above, the Aqualung i300 also has all the other usual features – dive log mode, total number of dives logged, a conservative factor setting (which lets you make the computer more conservative), metric/imperial adjustments and the ability to sync with a computer with an optional cable (this lets you download your dives for review on a computer or online dive log software, and also lets you upgrade the firmware of the device if need be) and auto-on – although for some inexplicable reason, you actually have the ability to turn off the ‘auto-on’ function, if you so desire.

Lastly, the i300’s Free Diving mode is quite robust: not only does it includes things like a Countdown Timer (before you start your immersion), but the computer actually tracks your activities in Free Diving mode. So that means you can switch from Free Diving mode to one of the Diving modes (Air or Nitrox) at any time – many other computers, including several Suunto models, require a 24-48 hour waiting time before letting you switch modes.

THE ALGORITHM

All of this is well and good, but ultimately, the main purpose of a dive computer is to help you plan and execute your dives. How good is the i300 at this?

Let me take a step back and sign a paean to Suunto dive computers. They are one of the heavy-weights of the dive industry, and with good reason – sophisticated computer models, workhorse reliability and smart interfaces. However, the big knock against them has always been how overly conservative they are – they use a very advanced model called RGBM, which tries to predict and minimize silent bubble buildup in the body, but the downside to this is that your dive time is greatly reduced, especially on repetitive dives.

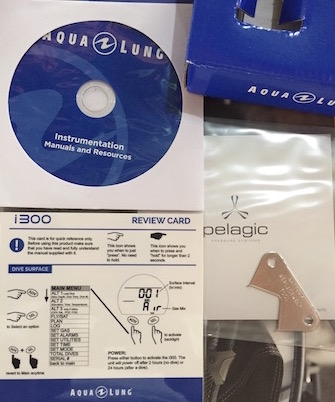

The i300 is made by Pelagic Systems – who also make dive computers for Oceanic, Mares and others, and who are one of the leaders in developing decompression algorithms. The i300 uses their PZ+ algorithm, which is a moderately conservative algorithm, slotting in between the liberal DSAT model (also created by Pelagic) and Suunto’s conservative RGBM model.

So in theory, this should give you more bottom time, especially on repetitive dives.

But hold on – isn’t it better to have a more conservative computer? I sort of agree with that – their extra conservative model is the reason we use Suuntos in our dive center, after all.

However, the decision-making for a dive center is going to be different from the decision-making for an individual: we have to take into account divers of all body types, fitness level, age groups, health levels and abilities. You only have to take into account yourself.

And the inescapable fact is that millions of people have been diving safely for years using variations of the Buhlmann model (which is the compartment-based model that you learn in Open Water and even Divemaster), of which the PZ+ is a derivative. So at what point is a computer conservative enough?

Suunto themselves recognizes it to some degree – on their higher end computers, such as the D9, they offered a setting which would let you make the computer less conservative.

Generally, my belief is this – unless you have a condition which requires you to be more conservative when it comes to DCS (age, fitness, overweight), the PZ+ algorithm is going to be more than adequate at keeping you safe – just be careful about watching your ascent rate, give yourself atleast an hour between dives and follow all the concepts of safe diving that you learn in Open Water, and you are good to go.

TESTING THE COMPUTER IN THE WATER

Over the past few days, I have taken the computer for a bunch of dives, along with my Suunto D9TX and a Suunto Zoop from the dive shop. To test how the computers responded to various diving situations and emergencies, not only did I do a day of regular diving, but I also took all 3 computers into decompression, and did a day of reverse profiles (a shallower dive first, a deeper dive second).

The computer behaved pretty much as i expected: on the first dive, I got a bottom time that was somewhere in between my D9TX (which has the reduced RGBM algorithm) and the Zoop (which has the full RGBM algorithm). The difference between all 3 computers was fairly small. On the second dive however, the i300 gave me a little bit more bottom time than the D9TX, and both gave me significantly more time than the Zoop – this is pretty much what I expected, given the algorithms.

The backlighting worked well, the tactile buttons were a pleasure to use, and all the automatic features of the computer worked precisely as they were supposed to. And the readout is very clear and easy to read, with all the essential information available at a single glance.

On the reverse profile day, the same held – all 3 computers gave readouts that were ‘sensible’, with similar bottom times as earlier.

On the decompression dive, there was a significant variation, however. I went down to past 40m and hung around till all 3 computers went into deco (no significant differences in bottom time here) and started to ascend once both computers were showing me 5′ of ascend time. As i ascended to a shallower depth and the controlling compartment changed, the Sunntos gave me credit for off-gassing on the faster compartment and the deco obligation cleared by the time i was at 15m. However, the i300 obstinately kept that deco clock ticking till I ascended to shallower than 10m.

This is a key difference – the Suuntos are designed for decompression diving (provided you are trained and qualified to know how to use them for this), whereas the i300 is strictly for recreational, no-deco dives (and it doesnt pay any attention to that ‘recreational deco’ nonsense) – So someone who is a technical diver or planning to become one may prefer a different computer. However, for the vast majority of recreational divers, this isn’t such an issue. You shouldn’t be going into deco anyway.

CONCLUSIONS AND FINAL THOUGHTS

2 weeks ago, if you had asked me to recommend an entry-level computer, I would have blindly said Suunto Zoop/Vyper – why? Because i am a long-time Suunto user – and Suunto is also the brand that we use in the dive shop, with excellent results.

However, while the Zoop still makes sense for the dive center, I think that for an individual diver, the slightly less conservative algorithm of the i300 makes it a better buy, especially given that prices are comparable.

There are a couple of cheaper options out there, such as the various 1-button dive computers like the Mares Puck. However, going back to what i wrote earlier about the difference between ‘best entry level’ and ‘cheapest’ – single button interfaces are a pain in the rear. Given that the monetary savings would have been very modest, I ruled those out.

There are also more expensive options out there – what a greater price gets you is a smaller form factor (so you can wear it like a wrist watch – which is actually a really good thing: it goes with you whereever you go, so you are sorted if you make a last-minute decision to go diving somewhere), air integration via optional tank transmitter (so you can see how much air you have left, both in bars and time, based on your breathing rate), an in-built digital compass (that’s nice to have for serious divers and pros) and, at the highest end of the scale, the ability to switch gases between various nitrox and helium blends and rebreather modes (useful for technical divers).

All those features are nice to have, and if budget allows, by all means go for it. A Suunto D6 or equivalent is a great buy in that price range. But if you are a casual recreational diver who is not looking to spend a huge amount of money on unnecessary gear, the Aqualung i300 gets my vote as the first piece of scuba gear you should own.

Buy the i300 at a special price