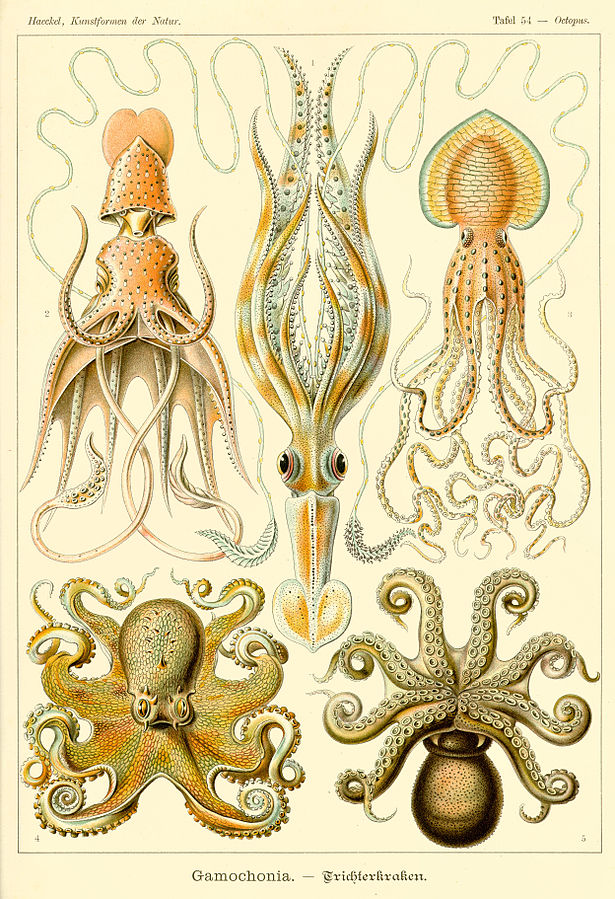

Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) juggled many professional hats during his life – he was a professor, biologist, philosopher, physician, and in the middle all that, he found the time to be a phenomenal artist as well. He is known for his enormous contribution to science, through the several new species he discovered, scientific concepts he theorized and biological terms he coined. He is also admired across various disciplines for his exquisite and influential collection of illustrations known as the ‘Kunstformen der Natur’ or ‘Artforms in Nature’ (sketched and painted between 1899 -1904).

If you are looking at any of these plates and admiring them for their abstract beauty or commending Ernst Haeckel for his marvellous attempt at science-fiction, take a look again. These are all real marine animals. They actually exist in these very shapes, patterns and forms. Ernst Haeckel observed and appreciated that in these underwater beauties; several decades before the advent of recreational SCUBA diving.

What do all these animals have in common? On careful observation you will notice that, yes they are all stunningly beautiful, there is inherent symmetry, but also, they are all types of ‘invertebrates’. They are all animals that lack a vertebral column or a backbone/spine inside their bodies.

Speaking of invertebrates, I never did understand the figurative use of this term in our society. To call someone a ‘spineless’, ‘invertebrate’ is to describe them as weak, cowardly, inadequate or ineffective. How did this association come to be?

Over 97% of animals on this planet are spineless, especially in the ocean. Some of the most venomous (box jellyfish), strongest (mantis shrimp), smartest (octopus), fastest reflexes (mantis shrimp again!), largest (giant squid), cutest (alright, this one is heavily subjectiveJ) are some form of marine invertebrate or the other.

A barrel sponge (Xestospongia testudinaria) can dwarf you despite your tank and fins

Vandit Kalia @vanditkalia

When reading about evolution and biology today we learn that, more and more, science doesn’t consider evolution to be progressive. Meaning to say that through the course of geological time, being older or having appeared first is no longer considered ‘primitive’ and being more newly evolved doesn’t make you necessarily ‘advanced’. Scientists now prefer to use terms such as ‘ancestral’ and ‘recent’ instead, with much less value judgement. Take sponges for example. Sponges consist of hollow cavities held together by protein fibres and they have numerous different types of cells, to filter food from water that is brought in and sent out. Sponges constitute some of the oldest animals to have ever lived (fossils as old as 640 million years old), and they still exist, all of 9,000 species of them.

A wise old coral colony

Gunnhild Sørås @gunnigullet Vikas Nairi @vikasnairi

Backbone-free animals are everywhere, and some of them literally shape our world. During the journey of a single dive in a shallow reef, we are immersing ourselves into a world whose multi-dimensional foundation, was built over millions of years, by the remarkably and astonishingly, spineless coral. Stony coral get a majority of their energy from their in-house photosynthetic symbionts and use it to put down calcium carbonate skeletons, layer by layer, that are strong enough to last years, centuries, and millennia. Corals live and lay the foundation of coral reefs, and then everyone else, from feather-duster worms to fish, start to step in to look for ways to build their own lives. An ecosystem is formed.

A closing sea anemone

Chetana Babburjung @chutney_babburjung

Through the course of your dive, you will surely find yourself smiling at clownfish in their anemones. Unlike a majority of their coral cousins which live as colonies of polyps, sea anemones are typically singular polyps lined by a whorl of stinging tentacles. Hidden in the centre of the anemone, if clownfish will allow you to see it, is an opening that is its singular window to the outside world- mouth and anus. It happens rarely and very difficult to catch with the naked eye, but sea anemones can move.

A peacock tail anemone shrimp busy on its host anemone

Gunnhild Sørås @gunnigullet

Anemones are cheerful hosts that collaborate not just with clownfish, but a variety of crustaceans, especially anemone shrimps and crabs that promise to help the anemone stay clean in return for a home.

Nudibranchs, a cryptic treasure.

Gunnhild Sørås @gunnigullet

Some of the more cryptic treasures to look out for on a reef are sea slugs, who are now coming out of the shadow of their celebrity cousins-the octopus. Among the mind-blowing diversity of sea slugs, nudibranchs are unique in that they breathe through gills placed outside their body (hence the name). While they have a versatile diet, some of them love eating fern-like hydroids. Hydroids just like their relatives -coral, anemones and jellies- are laced with stingers. No matter, Aeolid nudibranchs eat them anyway, carefully pocketing the stingers for later use as self-defence. Similarly sap-sucking slugs feed on algae but extract the algal pigments and keep them alive in their bodies for their own personal photosynthetic use. Is that ingenious, or is that ingenious?

Ernst Haeckel was particularly taken by the symmetry he saw in nature. A classic example for us would be- Echinoderms. A group found exclusively in the ocean, echinoderms are the sea stars, feather stars, brittle stars, urchins, cucumbers and several other unbelievable but underappreciated marine invertebrates (and therefore warrant a separate feature altogether).

A mollusc larva dancing in the blue

Vikas Nairi @vikasnairi

A typical shallow dive might last forty-five minutes to an hour and we may still not be ready to ascend to the surface, even though the gases in our tanks and bodies might dictate otherwise. But wait, the dive isn’t over yet. Safety stops are the best time to connect with bizarre but brilliant drifting creatures, as we hover in an endless soup of plankton.

At the end of the day, if Boris Johnson were to ever call me a “supine invertebrate jelly”, I think I might just say, thank you.

Watch this space for our next showcase on the underwater lives of the Incredibles.

The author, Chetana is a PADI divemaster and resident biologist at DIVEIndia in the Andaman Islands. She is an alumnus of the Masters program at the Wildlife Conservation Society -India program and National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bengaluru. She has been diving and exploring the Andaman Islands since 2013. She is also deeply excited about forests, birds, reptiles and amphibians.